On January 31st 1953 the United Kingdom experienced one of its deadliest maritime disasters when the Princess Victoria attempted to make the crossing from her home port of Stranraer in Scotland, to Larne in Northern Ireland.

It’s a short route, less than 45 miles, and a pleasant journey in good weather, but this crossing was attempted during the most severe weather event to hit the UK in a century: the storm surge that cause of the 1953 North Sea flood. Hit by the storm, the Princess Victoria was unable to weather the violent waves that swept her off course. She sank with the loss of 133 lives. 44 survived.

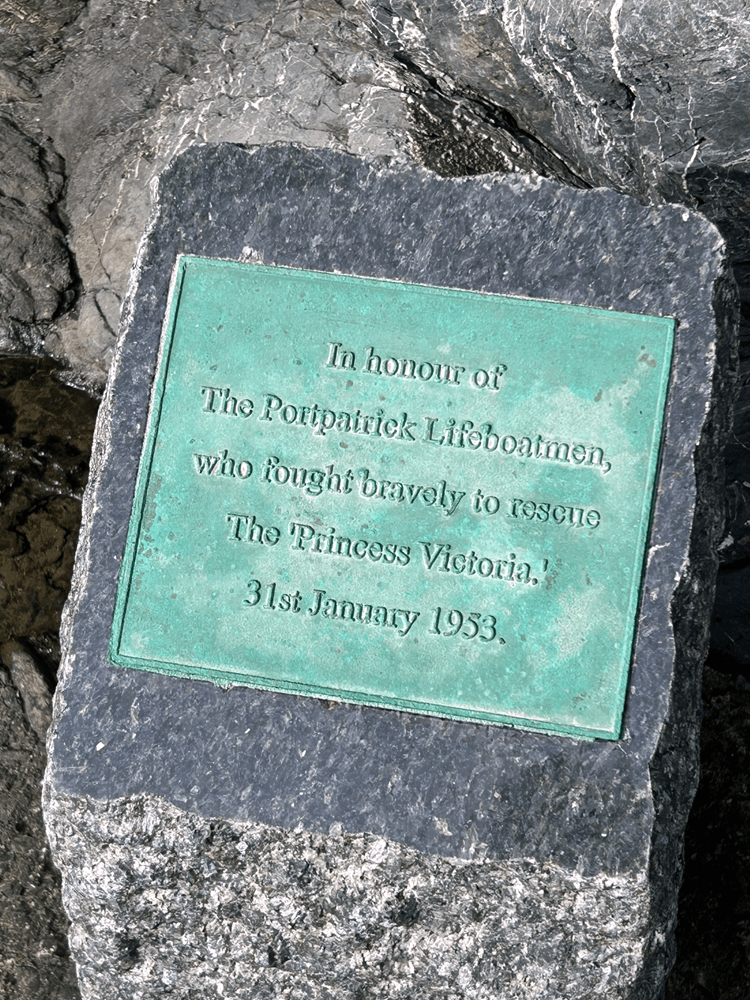

This is my local history, but I was unaware of it until I visited Portpatrick a few weeks ago. There, I saw a sculpture that was disturbingly memorable: two clawing hands reaching up desperately from the waves to grasp the edge of a boat. The plaque below read: In honour of the Portpatrick Lifeboatmen who fought bravely to rescue the Princess Victoria. 31st January 1953.

Such an evocative sculpture, and my lack of knowledge about event prompting it, meant I looked it up as soon as I got home. And I wanted to share the story, because it was such a devastating tragedy, because beyond the towns it most affected it’s largely forgotten, because there were those who risked their own lives to try to save others, and I wanted to write their names as a small act of remembrance for their bravery.

The Princess Victoria was a new type of ship, a roll on-roll off ferry, and the first of her type to travel in British coastal waters. Her captain was James Ferguson, who’d captained ferries on the Stranraer-Larne route for 17 years. Despite the warning of gale force winds, on 31st January 1953 he decided to leave port at 7.45 am. The ship headed out of the sheltered Loch Ryan, where the danger of the weather wasn’t so obvious, but on reaching the North Channel the car deck quickly began to flood as the stern doors had not been properly secured, and despite the crews’ efforts they could not be closed. The extreme weather prevented a return to Loch Ryan, so Ferguson chose to head for Northern Ireland via a course that would least expose the stern to the impact of the waves.

At 9.45 am she radioed for help, asking for tugs (none were available as they were assisting other vessels). At 10.32 am she sent an SOS. At 1.08 pm the order to abandon ship was given. Just before 2.00pm the ship sank beneath the waves.

When the SOS was received the Portpatrick lifeboat, Jeannie Spiers, immediately left harbour. She headed out into the worst storm to hit Britain in the 20th century in a boat 46 feet long and 13 feet wide. It’s the bravery of these men that the Portpatrick memorial remembers. Seeing those massive waves, feeling those gale force winds, and heading straight into the storm to try and save lives.

But the lifeboat couldn’t find the Princess Victoria, and eventually returned to her home port. Sleet and snow with gale force winds meant poor visibility, and the sinking ship reported her position some miles from where she actually was. Her real position wasn’t given until 1.45 pm when the crew caught site of the Irish coast.

Several merchant vessels arrived on the scene first, but they were unable to rescue survivors and instead tried to shield them from the worst of the weather. It was not until 4.00pm, with the arrival of the lifeboat Sir Samuel Kelly, from Donaghadee, that any survivors were brought to relative safety. Few of the Princess Victoria‘s lifeboats remained afloat. The first lifeboat to leave the ship had all the women and children aboard, but shortly after launch the boat had capsized. None aboard survived.

None of the Princess Victoria‘s officers survived either. All had gone down with the ship. The radio officer, David Broadfoot, had stayed at his post until the end, and was posthumously awarded the George Cross. Captain James Ferguson had been on the bridge, standing at salute.

When the destroy the HMS Contest arrived, her crew were able to rescue more survivors from the sea. And in a truly mind-blowing act of heroism, Rear-Admiral Stanley McArdle tied a lifeline around his waist and dived into the sea when he saw a man struggling to hold onto a raft. Bringing the man back to the ship’s scrambling net exhausted him. And so Chief Petty Officer Wilfrid Warren dived in to, and the three men were all, eventually, safely brought back onboard.

Most of the dead came from two small towns, Stranraer and Larne, and I can’t imagine how devastating it must have been for those communities. It’s a particularly difficult disaster to read about as it’s filled with points where a single choice could have averted the tragedy, or a single piece of luck. What there was was the bravery of the Princess Victoria’s officers and crew, and the bravery of every vessel that went looking for the ship. It’s humbling to know what so many were prepared to risk on the chance they could find the a single floundering vessel amidst such a terrifying storm.

So, thank you Portpatrick memorial, for remembering, and for allowing me to remember.

Discover more from Lizbeth Myles

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1

1